The crash of Northwest Flight 2501 into southern Lake Michigan on June 24, 1950, marked the worst American aviation accident at the time when all 58 people aboard lost their lives. The wreckage could not be found by authorities, the cause of the crash could not be determined, and the accident was soon forgotten. More than half century later, Valerie van Heest became interested in the accident when research conducted in 2003 by the Michigan Shipwreck Research Association (MSRA) , cofounded by van Heest, determined that the aircraft had gone down in the same general vicinity as a number of number of lost ships the group hoped to find. Author and explorer Clive Cussler learned of MSRA’s research and proposed a joint venture expedition to search for the aircraft wreckage in 2004.

The crash of Northwest Flight 2501 into southern Lake Michigan on June 24, 1950, marked the worst American aviation accident at the time when all 58 people aboard lost their lives. The wreckage could not be found by authorities, the cause of the crash could not be determined, and the accident was soon forgotten. More than half century later, Valerie van Heest became interested in the accident when research conducted in 2003 by the Michigan Shipwreck Research Association (MSRA) , cofounded by van Heest, determined that the aircraft had gone down in the same general vicinity as a number of number of lost ships the group hoped to find. Author and explorer Clive Cussler learned of MSRA’s research and proposed a joint venture expedition to search for the aircraft wreckage in 2004.

Initially, the only primary information about the flight came from the Civil Aeronautics report, a 4 page, 6000-word document that provided information about the aircraft, the flight, and the transmissions between the flight operators and the crew. Newspaper accounts provided other limited details. In time van Heest, who adopted this as a passion project, amassed a collection of primary information never before considered in the aftermath of the accident and years later had her narrative nonfiction novel, “Fatal Crossing,” about the aircraft’s disappearance and the group’s effort to find the wreckage published.

THE FLIGHT, DISAPPEARANCE, AND INITIAL SEARCH AND RECOVERY OPERATION

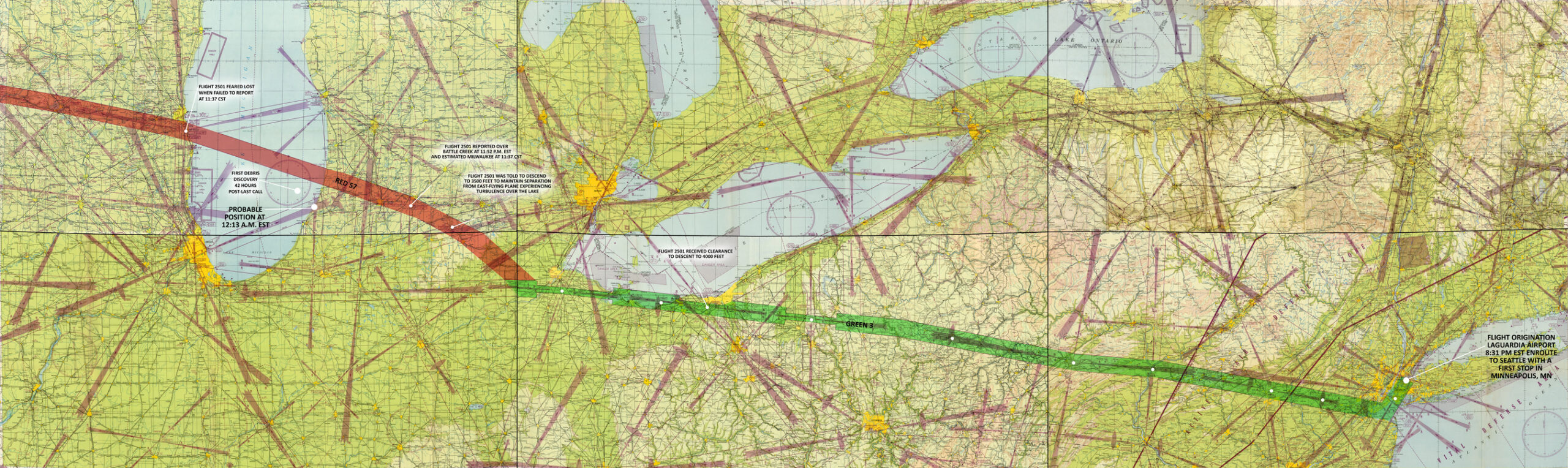

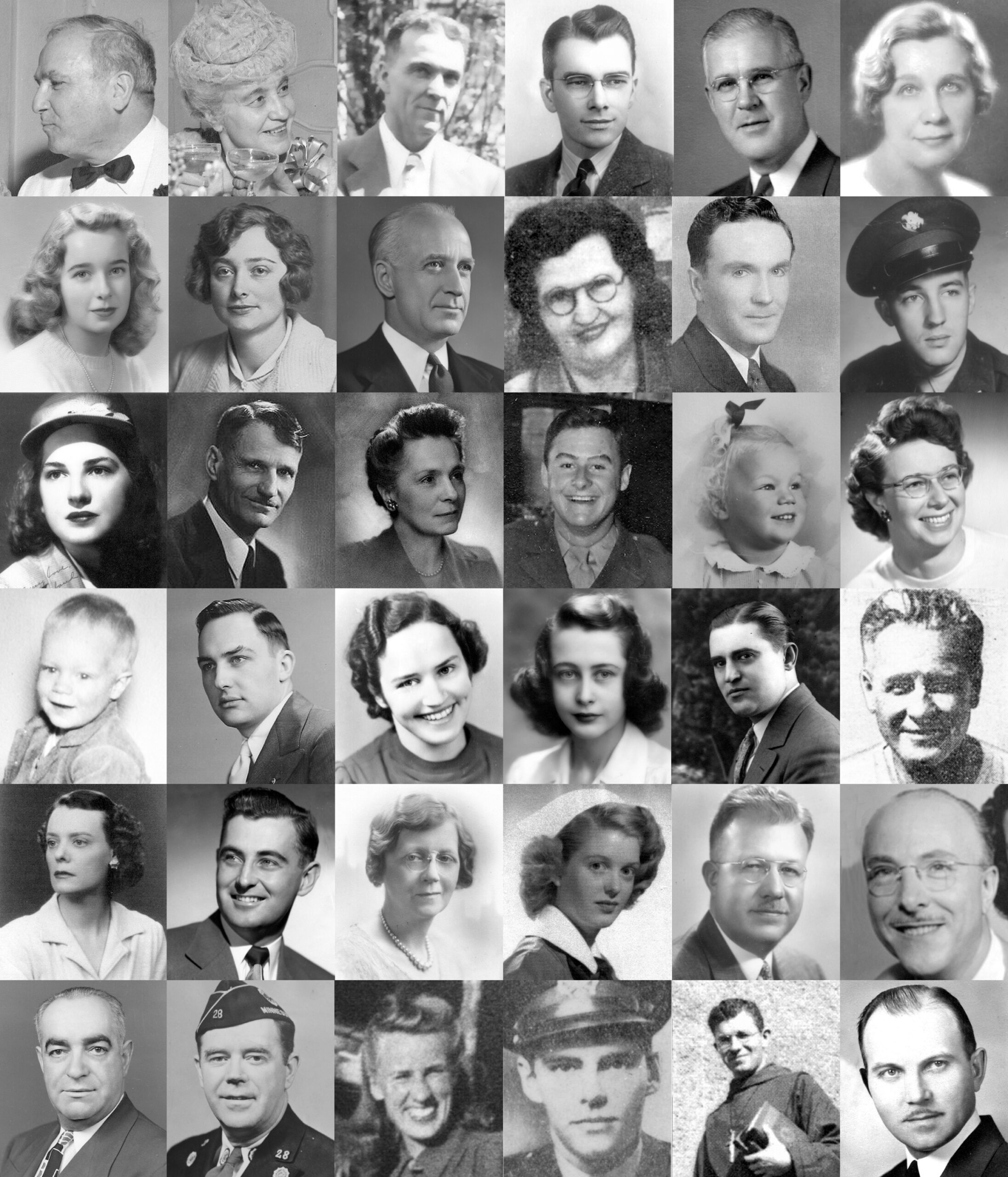

On Friday, June 23, 1950, Northwest Airlines Flight 2501, operating with a DC-4, departed New York’s LaGuardia airport at 8:30 PM EST and headed west to Seattle Washington, with planed stops in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and Spokane, Washington. Captain Robert C. Lind served as pilot with Verne F. Wolfe as first officer and Bonnie Ann Feldman as stewardess. There were 55 passengers, including 27 women, 22 men, and six children.

Before takeoff, Captain Lind was advised of thunderstorms over Lake Michigan, but other planes did not report severe turbulence and the flight was cleared for takeoff. At various points in the flight, Lind was directed to a lower altitude to maintain clearance with other flights. As the DC-4 passed over Battle Creek, Michigan at 11:51 EST, at 3500 feet, it entered the storm front. Captain Lind notified Northwest’s Air Traffic Control Center at Chicago by radio that he estimated he would pass over Milwaukee 46 minutes from that time. His course was due to cross Lake Michigan in air corridor “Red 57” which runs from Glenn, Michigan, on a northeasterly course towards Milwaukee and Minneapolis. At that time, however, a squall line that had developed earlier that afternoon reached the region of Lake Michigan. By midnight the squall line was raging south down the lake. Lightning flashed between the cells of the storm. Winds whipped up the lake’s surface.

Although it is unclear what Captain Lind did when he reached the lakeshore and inevitably saw or felt the storm, at 12:13 AM EST when in the vicinity of Benton Harbor, Michigan (20 miles south of Airway Red 57), Lind requested a descent to 2500 feet, but did not indicate his reason for the request. Air traffic control denied the altitude change due to other traffic in the area. That was the last communication from Flight 2501.

By dawn’s light, it became clear that Flight 2501 had gone down, probably in Lake Michigan. Initially an oil slick spotted near Milwaukee led authorities to believe it crashed there until a commercial fisherman encountered a large floating field of debris off South Haven, Michigan. The Coast Guard and the Navy initially mounted a rescue operation off South Haven, but soon realized that no one had survived. Instead Coast Guard crewmen began recovering floating debris, city and state authorities began recovering debris that washed ashore, and the Navy began searching for the submerged wreckage. After five days, the search ended with the authorities declaring they had been unable to locate the crash site. With the loss of 58 people, this became the worst aviation accident in US history at the time.

One month later the Civil Aeronautics Board conducted a hearing in Chicago, interviewing over 30 individuals, including shore based witnesses, Northwest Airlines personal, and Coast Guard and Naval personnel over two days. In January 1951, the board issued a final report based on that hearing, concluding that it could not establish a cause for the accident, and only provided a probable location for the crash, 18 miles north, northwest of Benton Harbor, Michigan, oddly far outside any established airway.

THE RENEWED SEARCH EFFORT

Ralph Wilbanks of NUMA with MSRA team

In 2004, before the Michigan Shipwreck Research Association could begin its expedition to try to locate the aircraft’s remains, nationally acclaimed novelist and explorer Clive Cussler contacted the organization. He had heard of the flight, MSRA’s interest in finding it, and he proposed a joint venture between MSRA and his nonprofit the National Underwater Marine Agency (NUMA), which had located many dozens of lost vessels over the prior two decades, to search for the wreckage. To undertake this effort, Cussler would send his side scan sonar expert Ralph Wilbanks, a marine archaeologist and owner of Diversified Wilbanks, Inc., to South Haven, Michigan, to work with MSRA, which would be responsible to for compiling the research and developing a search grid.

The joint effort began in the fall of 2004 with the team searching where the C.A.B estimated the crash had occurred, but the search was unsuccessful. NUMA and MSRA agreed they would need to expand the search area to some 600 square miles based on the evidence of floating debris. To narrow down the search, MSRA began working with renowned Lake Michigan scientist David Schwab, then with NOAA, who developed a more defined, smaller e search area based on drift analysis and hindcasting. Cussler too began working with outside experts who studied ocean drift theories, and their theories differed from Schwab’s. However, because Cussler funded the search, he had ultimate authority where to search.

The joint effort began in the fall of 2004 with the team searching where the C.A.B estimated the crash had occurred, but the search was unsuccessful. NUMA and MSRA agreed they would need to expand the search area to some 600 square miles based on the evidence of floating debris. To narrow down the search, MSRA began working with renowned Lake Michigan scientist David Schwab, then with NOAA, who developed a more defined, smaller e search area based on drift analysis and hindcasting. Cussler too began working with outside experts who studied ocean drift theories, and their theories differed from Schwab’s. However, because Cussler funded the search, he had ultimate authority where to search.

In 2006 Valerie van Heest was contacted by the family of a victim, which had heard about the joint team’s search effort. That contact ultimately led Van Heest on a more personal mission to track down the families of the victims so that, in the event of a discovery, she could provide those families with the details of the discovery before news could reach the media. In time she located 52 of the 58 families, and she learned the intimate details of each passenger’s reasons for being on the flight and how their losses affected their families. These emotional stories led Van Heest to begin considering writing a book, which escalated her research. From 2006 to 2012 she also located thousands of pages of courtroom testimony from two wrongful death suits, tracked down dozens of other individuals, all seniors, who had specific first-hand testimony about the incident, and located an unmarked grave where the recovered remains of victims had been buried. Over those years she drafted a manuscript that she presumed might be published upon the discovery of the wreck. Clive Cussler backed her decision to write a book.

From 2004 to 2013, the MSRA/NUMA team covered some 450 square miles, and did not locate the wreck, but did find ten significant shipwrecks. Van Heest wrote about some of those wrecks in several of her other books and in magazine articles, gave hundreds of in person lectures, and she appeared on television talking about many of these shipwrecks.

THE MUSEUM EXHIBIT FATAL CROSSING

In 2016, Van Heest had an opportunity rarely afforded authors or explorers. As a professional exhibit designer, she was hired by the Michigan Maritime Museum to develop an exhibit based on the contents of her book Fatal Crossing. It ran at the South Haven-based museum from 2014 – 2018 and then moved to the Yankee Airforce Museum in Belleview, Michigan, where it is currently on exhibit.

In 2016, Van Heest had an opportunity rarely afforded authors or explorers. As a professional exhibit designer, she was hired by the Michigan Maritime Museum to develop an exhibit based on the contents of her book Fatal Crossing. It ran at the South Haven-based museum from 2014 – 2018 and then moved to the Yankee Airforce Museum in Belleview, Michigan, where it is currently on exhibit.

THE CONTINUED SEARCH

MSRA made a decision to continue the quest independently in 2014, and Clive Cussler, motivated by the organization’s tenacity decided to send back his team for three more expeditions that took place in 2015, 2016, and 2017, but the wreckage remained elusive. Since 2018, MSRA is continuing the effort independently, focusing solely on the area defined by David Schwab’s hindcasting reanalysis, which he further narrowed down in 2019.

MSRA made a decision to continue the quest independently in 2014, and Clive Cussler, motivated by the organization’s tenacity decided to send back his team for three more expeditions that took place in 2015, 2016, and 2017, but the wreckage remained elusive. Since 2018, MSRA is continuing the effort independently, focusing solely on the area defined by David Schwab’s hindcasting reanalysis, which he further narrowed down in 2019.

APPEARANCE ON DISCOVERY CHANNEL’S SHOW “EXPEDITION UNKNOWN”

In 2018, Van Heest appeared in an episode of the hot television show Expedition Unknown starring explorer Josh Gates. During filming Van Heest mentioned her team’s efforts to search for Flight 2501, and Gates expressed interest in joining her and MSRA on their continued search for the airplane wreckage in the hopes of developing an episode about the project. The episode, filmed in August 2019, debuted in February 2020 as a 2-hour special, in which Van Heest, her husband Jack, and David Schwab were featured, as well as MSRA divers Todd White and Jeff Vos, and other individuals Valerie had interviewed for her book. The episode called “The Vanished Airliner,” aired in Season 6 and interpreted Van Heest’s book “Fatal Crossing” for television.

In 2018, Van Heest appeared in an episode of the hot television show Expedition Unknown starring explorer Josh Gates. During filming Van Heest mentioned her team’s efforts to search for Flight 2501, and Gates expressed interest in joining her and MSRA on their continued search for the airplane wreckage in the hopes of developing an episode about the project. The episode, filmed in August 2019, debuted in February 2020 as a 2-hour special, in which Van Heest, her husband Jack, and David Schwab were featured, as well as MSRA divers Todd White and Jeff Vos, and other individuals Valerie had interviewed for her book. The episode called “The Vanished Airliner,” aired in Season 6 and interpreted Van Heest’s book “Fatal Crossing” for television.